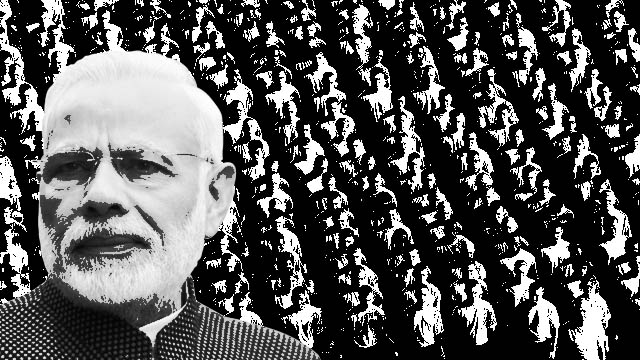

Authoritarian populists and their politics – Part I

Since a decade or so democracies of the world have been experiencing the rise of right-wing authoritarian populist leaders (RWAP). The result has been, their highly personalised style of leadership and rule not only destroy the democratic constitutions and traditions of the countries they rule but also exhibit serious implications on their foreign policy and international engagements. Since the rise of such leaders happens through the democratic process itself, this phenomenon is termed as “democracies devouring themselves.” In this two-part article, I discuss the personality and politics of such leaders and the social context that provided the fertile ground for their rise all over the world.

For over a decade or so the world has been witnessing the rise of right-wing authoritarian populist leaders. The way these leaders use populist propaganda, and even fake news, to come to power, and most importantly how they employ authoritarianism to rule their nations, more and more people are concerned about the fate of democracies in the world. From the outset, it looks, that the national ethnocultural majorities, facing a variety of social changes and increased feelings of collective status threat, have started to support, overwhelmingly, the majoritarian identity politics of the populist leaders.

This situation is enabled by political and media discourses that have “channelled such threats into resentments toward elites, immigrants, and ethnic racial and religious minorities, thereby activating previously latent attitudes and lending legitimacy to radical political campaigns that promise to return power and status to their aggrieved supporters”. (Bonikowski, 2017, p 181)

Populist leaders, depending on the popular salience of the issue of their country, have benefited from this anxiety. They promise to get rid of immigrants or control immigration (as with Donald Trump in the USA and any number of others in the European Union countries); punish and put the minorities in their rightful place (as second class citizens) as is going on under the leadership of Narendra Modi in India, Mahinda Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka; and promise to get rid of the Leftists/communists/the elites from the body politic as is happening in South America, Turkey and elsewhere.

These leaders have been riding high on power in their respective countries exhibiting their authoritarian, controlling and narcissistic personalities; and shaping the nations in their own image and likeness. These developments happening around the world are viewed by a social scientist named Shawn Rosenberg as weaknesses of the democratic system itself where, at a certain stage in their history, democracies tend to devour themselves.

Focus on Leadership and Strategies

To understand the phenomenon and find the causes, many have been focussing on the strategies and personalities of the leaders of such populist movements and the ideology of their political parties. This is one of the popular academic and analytical approaches. However, not much research has taken place about the other issues that contribute to this phenomenon, namely, the national environment or the nature of the citizenry and the role of the liberal classes as well as the socio-economic policies adopted by them while in power.

Hence, one must ask the question: does the charisma and the leadership qualities of populist leaders the sole reason for their spectacular rise or does the incompetence of citizens to understand the demands of democracy and the failure of the elites within the system also play a crucial role? How far is this symptomatic of Indian democracy under Modi’s rule? Are there ways to counter this decay through democratic practices?

Focusing on India under Modi, I discuss this phenomenon in two parts. The first part will deal with the characteristics of right-wing authoritarian populist leaders and the main features of their politics. The second part will focus on the national environment (the failure of citizens, and the elite along with their role in promoting neoliberal globalisation and the rise of identity politics) that prepared the ground for Right-Wing Authoritarian Populism (RWAP) leaders to emerge.

Identifying the malaise and the chief proponents

When social scientist, Shawn Rosenberg, claims that democracies in many countries are devouring themselves he gives examples by identifying Trump (USA), Modi (India), Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Turkey), Victor Orban (Hungary) or Jair Bolsenaro (Brazil), etc, as right-wing populists (Rosenberg, 2019). Rosenberg sees this state of declining democracy “not as the result of fluctuating circumstances or a momentary retreat in the progress toward ever greater democratization… instead they reflect a structural weakness inherent in democratic governance, one that makes democracies always susceptible to the siren call of right-wing populism.” (Rosenberg, 2019, p 3)

He further argues that as countries “become increasingly democratic, this structural weakness is more clearly exposed and consequential. In the process, the vulnerability of democratic governance to right-wing populist alternatives becomes greater. Hence the conclusion that democracy is likely to devour itself”. (Rosenberg, 2019, p 3)

Explaining the phenomenon, he claims further that, more than the populist leaders themselves, it is the incapacity of citizens to understand and sustain democratic ways of being citizens that underlies the phenomenon. Rosenberg also blames the elites of democratic societies for their failure to mediate and educate the citizens in democratic practices that give way to right-wing populism. Other research on neoliberal economic practices and globalisation implicates the liberal elite for the rising disenchantment among the people with democracies and traditional leadership.

In the process, the vulnerability of democratic governance to right wing populist alternatives becomes greater. Hence the conclusion that democracy is likely to devour itself”

(Rosenberg, 2019, p 3)

Is there evidence to this effect?

Yes. If the second half of the 20th century was the golden age of democracy where if in 1945 there were 12 countries that were democracies by the end of the century their number grew to 87. But since the beginning of the 21st-century progress towards democracy has come to a sudden halt. Rosenberg suggests that vote share of the populist parties has increased threefold between 1998 to 2018. Most recent evidence shows that it is even more.

To prove his point, he cites rise in vote share of Right-wing populist parities in Europe and elsewhere. If one takes the case of India which had been a democracy ever since it gained independence from the British in 1947, the recent developments bear witness to this worldwide phenomenon.

Is India part of this phenomenon?

As India grew politically, economically, and socially more democratic, it turned out to be a fertile ground for Modi’s right-wing populism. Between the 2014 and 2019 national elections the right-wing populist leader Modi’s party Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) increased its vote share from 31.1% to 37.4% respectively. As a result, it has won an absolute majority in the parliament winning 282 and 303 seats respectively in those two elections.

This rise in support is attributed not to the party but to the personality of Mr Modi. The evidence of it is that in the state level elections, held just after the 2014 national elections, the BJP projected Modi as the face and won nearly 70% of the states. So, the populist leader and his or her personal charisma along with the populist agenda are perceived to be crucial ingredients of success. A similar trend has been observed worldwide where right-wing populists have come to power using their personal charisma and rhetorical flourish (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018). What accounts for their success and how should one understand this phenomenon?

What is right wing populism?

Some social scientists and conservative thinkers would argue that RWAP is an ideological cousin of Conservatism. But, according to Rosenberg, the intellectual roots and underlying logic of RWAP must be “best understood as an outgrowth of the fascist ideologies of the early 20th century as evident in its rejection of liberal democratic conception of the nation and citizenship.” In this context Rosenberg treats this ideology in its neo-fascist form. For him, RWAP can be identified in three clusters of political attitudes: populism, nativism, and authoritarianism (Rosenberg 2019).

Under populism it claims to represent ‘we the people’ which very often refers to the majority population as against a more defined enemy who is not considered as the “people”. In this ‘not people’ category belong the minorities, social, political, economic, and intellectual elite as well as the opposition parties. In the case of India this group of “not the people” contains Muslims, Christians, Dalits, political opposition, Leftists, women, and all kinds of dissenters against the government and its ideology.

In the Indian context, such dissenters are branded as ‘Urban Naxals’, terrorists, Jihadis, “anti-nationals”, sickulars, rice bags, missionaries, Maoists, and anti-Hindu. Elitesare specially targeted for being disproportionately powerful due to their status as upper class or caste, their (English) education and media power which supposedly give them disproportionate control over democratic processes such as elections, political discourse, and core governmental institutions.

In Modi’s words this class of people are identified as “Lutyens Delhi”, a posh area of New Delhi where most of the elite ruling class lives. This has been used to distinguish himself as someone from outside (Gujarat state politics) and someone who genuinely represents “the people.” To prove his credentials as someone from among the people and someone who identifies with the people, Modi used his purported childhood days of selling tea (“Chaiwallah”) at his father’s tea stall at a railway station and his backward caste lineage.

The second characteristic of RWAP, Nativism, can also be called ‘ethnonationalism’. In this cluster ‘the people’ are more clearly defined as those who share some core beliefs (especially religious), aspects of physical appearance (racial), and ethnic origin (real or mythical). While there is a process of defining ‘who we are’ the very process also defines who we are not and who falls outside this group. In the context of India today, for the BJP government, this question is settled by its Hindutva ideologues from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), especially by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in his major treatise “Hindutva: Who is a Hindu”(Savarkar 1969).

It’s only the Hindus (this generally excludes Dalits), whose Pitr Bhoomi (fatherland) is India, who are ‘the people’ and Muslims and Christians are the ‘non-people’ because their holy lands are not in India. Consequently, in the purported Hindu Rashtra (Hindu Nation) these minorities are second class citizens.

The most recent ‘Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019’ (CAA, 2019) passed in the Indian Parliament and the process of granting citizenship of the country to refugees on the basis of their country of birth and religion is a major step towards achieving the ‘majoritarian ethno-nationalist’ state (Hansen 2019). This approach is unacceptable in a constitutional democracy where citizens are defined neither by their origins, religious practices, beliefs, appearance nor behaviour, but based purely on their legal status as citizens.

This is not acceptable to the new Hindu majoritarian regime in Modi’s India. That’s the very reason, in the ongoing Delhi Assembly Election of February 11th 2020, at rallies and media discourses, those who are fighting for the existing secular, democratic constitution and opposing the CAA were being branded by the ruling Hindutva party, the BJP, as “traitors, terrorists, disruptors of peace, stooges of Pakistan and anti-nationals”.

Modi has achieved, sustained and remains in power through his anti-Muslim politics. His party’s anti-Muslim politics is so rabidly divisive and exclusionary that even the currently raging coronavirus pandemic is imputed to Muslims as the chief spreaders of the virus.

Modi’s disdain and hatred for Indian liberal secularists are expressed continually through his attacks against the main opposition party, Indian National Congress. The chief target of Modi and his party’s criticism is directed towards India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, for his purported liberal and secular policies. The other target is the Gandhi-Nehru family that played a pivotal role in India’s politics and power over the last seven decades. The other targets are the public intellectuals, journalists, universities and literary figures who oppose the majoritarian fascism and the populist ideology of Modi.

Right-wing populist leaders also exhibit multiple authoritarian traits

Authoritarianism has two aspects: conception of leadership and hierarchical conception of power. True to its fascist ideological pedigree, the leadership, especially the leader in whom the power rests, is viewed as the embodiment of ‘the people as a whole’. Hence, the individual’s will must be subservient to a single national purpose.

For instance, in the Indian context it is the establishment of the “Hindu Rashtra” (Hindu Nation) and to establish this imaginary ‘nation’. To achieve this goal everything, including the constitution and the institutions of the state must fall in line. Also, as the power is centralised at the top what follows is a delegation of power in different degrees to lower echelons in the hierarchy. This enables the leader to usurp complete control, supposedly for the purpose of achieving efficient governance. In India under Modi one can see this hierarchy and subservience in all spheres of administration. Even the corporate media is forced to toe this line.

Hence, under this conception of power, democratic ways of legal checks and balances are an obstruction to act on behalf of the people. Under these authoritarians, most of the constitutional bodies either become extinct or become subservient to the will of the leader. Recall, here, how Modi wanted to be unaccountable in the Rafale Jet scam, where he personally concluded a revised agreement with French giant Dassault Aviation, which most specialists and opposition parties claim is a corrupt deal.

A similar example is the PMCARES Fund, set up during Coronavirus pandemic which Modi does not want Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India to audit or bring it under the Right to Information Act (RTI) remit. One should also not forget how Modi came to power promising the national Lokpal Act but has consciously avoided enacting it so far. Such constitutional aberrations are undertaken because the populist leaders claim to derive their power directly from the people; because he, and not the party, who was the cause of popular support.

Hence, it is clear, that RWAP politics is a rejection of the structures of democratic governance and a challenge to liberal democracies. Why do democracies with a substantially long history in Europe, North America, India and elsewhere give way to right wing populist politics (leaders)? What kind of people or citizens are highly susceptible to right wing populist politics? How were the past ruling classes or liberal elites responsible for this state of RWAP to emerge? These questions will be answered in the second part of the discussion.

References

Bonikowski, B. 2017. Ethno‐nationalist populism and the mobilization of collective resentment. The British journal of sociology, 68, pp. S181-S213.

Hansen, T. B. 2019. Democracy against the law: reflections on India’s illiberal democracy. Majoritarian state: How Hindu nationalism is changing India, pp. 19-40.

Levitsky, S. and Ziblatt, D. 2018. How democracies die. Broadway Books.

Rosenberg, S. W. 2019. Democracy Devouring Itself: The Rise of the Incompetent Citizen and the Appeal of Right Wing Populism. In: Hng Hur, D.U. et al. eds. Psychology of Political and Everyday Extremism. Irvine, USA: UC Irvine.

Savarkar, V. D. 1969. “Hindutva; who is a Hindu?” Bombay: Veer Savarkar Prakashan.

Dr Samuel Sequeira is a Research Associate at Cardiff University, UK. A native of Karnataka, he had his MA at Mysore University (Karnataka) and had worked as an Editor of Konkani and Kannada newspapers. He has his PhD from Cardiff University where he researched on “South Asian Migrant Community living in Wales”. His current research is about the topic “Trauma of Civil War: Sri Lankan Tamil Experience”.