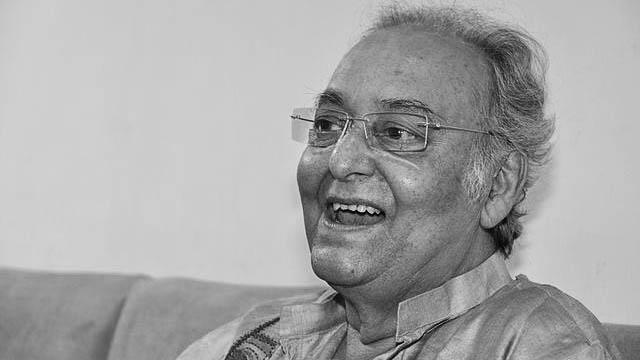

The entire Bengali Bhadralok society is appalled! Its much-cherished cultural wreath quietly lost one of its valuable flowers to the exuberant flow of time. Soumitra Chattopadhyay, the legendary film actor and winner of numerous awards, died on November 15th 2020, after a 40-day-long battle with different ailments, which started with his COVID-19 infection. Chattopadhyay was 85 years old. The Bhadralok is saddened.

Starting his film career with the legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray in 1959, Chattopadhyay has worked in over a few hundred films in a career span of 61 years and a few titles of his are still awaiting release. He has worked in some of those magnum opus films, as well as those quintessential “commercial” Bengali films produced by the Marwari-Gujarati comprador lobby and big corporates. Even in his 80s, Chattopadhyay was ebulliently working in the industry and delivering. As an actor, he not just won India’s highest award, the Dada Saheb Phalke Award, but also France’s highest award for artists and highest civilian award- the coveted Chevalier of Legion of Honor, which Ray also won.

While there has been a flood of obituaries and epitaphs are inscribed with words of glory, especially from a section of the left who hail the man for his life-long support to West Bengal’s former ruling party Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)], there is a need to draw a line of demarcation to ensure no spurious claims can now create a hagiography to farther a nefarious political agenda. Rather than showing unconditional obeisance towards the man and following the Brahminical feudal custom that calls for ceasing criticising someone after they die, it’s imperative to analyse Chattopadhyay’s role critically and materially.

A man is a product of his circumstances. His consciousness is influenced by his surrounding material world. He can act and respond to situations according to the beliefs and thoughts designed by his peculiar material conditions. Chattopadhyay was no different. Hailing from an upper-middle class family, Chattopadhyay was able to pursue a career in the film industry, like many other Bhadraloks, due to his caste-class privileges. People like Chattopadhyay helped the Bhadralok in retaining the caste-class hegemony of the bloc over the cinema industry.

As a brahmin, he naturally became acceptable to the Bhadralok audience and became a competition to his contemporary Arun Kumar Chatterjee, another brahmin Bhadralok known as Uttam Kumar in the Bengali cinema. The Bhadralok remained indulged in a timeless debate over who among the duo is the best. The Bhadralok, who didn’t allow the Namasudras––Bengali Dalits––and tribal people an inch inside their sacred “film industry”, revered icons like Chattopadhyay as he resembled them, spoke their words and tried to sound morally superior like them despite having roots in exploitation and appropriation of the labour of the oppressed masses.

Despite occasionally joining the leftwing movements in Kolkata against food inflation and the US aggression on Vietnam in the mid-1960s, Chattopadhyay distanced himself from the arena of cultural class struggle and also from the wave of Naxalbari movement––the spring thunder of India––and remained opponent of the movement like his mentor Ray. Though Ray and Chattopadhyay made some iconic films as per Bhadralok parameters, including “Hirak Rajar Deshe” (In Hirak Raja’s Land) in which the national emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi was criticised using layers, their films remained urban Bhadralok-centric and didn’t consider the Namasudras or the tribal people their audience.

While Ritwik Ghatak, a crypto-Trotskyist filmmaker, tried to project various sides of the untold pains of the exploited, Ray and his contemporaries remained aloof from them. Chattopadhyay maintained an inimical relationship with Ghatak due to the latter’s contradiction with Ray. The tussle even turned cantankerous over Ghatak’s inebriated condition and Chattopadhyay gloated the fact that he hit the director for the sake of Ray. Such Brahminical hegemonist bonding wasn’t questioned by the progressive Bhadralok custodians of Bengali culture.

Chattopadhyay was rather eulogised for his role as “Apu”, the eponymous character of the “Apu-trilogy” that became Ray’s magnum opus. “Apur Sansar” (The World of Apu) was the first film of Chattopadhyay and he became a superstar soon. Then came the iconic “Feluda” series from Ray. “Feluda”, aka “Prodosh Chandra Mitter”, is a Bengali Bhadralok private detective, whose tales would enthral teenagers and adults alike for generations. Ray illustrated “Feluda” using Chattopadhayay’s image and he was the protagonist in the original “Feluda” series in the 1970s.

Through “Feluda”, “Apu” or the much-famed “Udayan Master” of “Hirak Rajar Deshe”, or the adamant swimming coach in “Koni”, Chattopadhyay became typecast of the self-righteous Bhadralok. Chattopadhyay’s role helped the Bhadralok to imagine himself as he likes to– the self-righteous, intelligent, cultured and upholder of values. In reality, the Bhadralok is devoid of these and survives only by sucking the blood and labour of the toiling Namasudra and by appropriating the land, forests and water of the tribal people.

Chattopadhyay remained confined in films and took part in a few socio-political movements. He stayed a loyal ally of the CPI(M). When the CPI(M) cadres unleashed macabre atrocities against the peasants in Singur and Nandigram, who were opposing the forceful grabbing of their agricultural land by corporates, he stood by the side of the mercenaries. Chattopadhyay stayed away from all public protests against the CPI(M) and took a centrist position when he understood that the Left Front government will collapse.

Though he didn’t join the Bengali film industry’s dominant brigade that prostrated before Chief Minister Mamata Bandopadhyay since her ascension to power, he didn’t take any concrete position as well. At one point in time, along with Aparna Sen and other dignitaries, Chattopadhyay wrote a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, opposing the growing intolerance in India. Lastly, he joined the movement against the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Kolkata in 2019, but at the same time, despite having multiple films in his kitty, he did advertisements to promote astrology and gems. Stooping to such a nadir can be credited to the domination of Marwari-Gujarati comprador lobby in the film business, who want to reinvigorate the prevailing superstitions in the Bhadralok community for their own commercial and political gains.

It’s imperative to see that a Bhadralok left Chattopadhyay and his ilk, who get gun salute during funeral from the state machinery––which launches incessant wars to evict tribal people from their water, forest and land, which wants to disenfranchise millions of Namasudra refugees, which imprisons numerous intellectuals, writers, poets, activists for exhibiting dissent––have served that very state’s ruling classes. The Bhadralok need new faces and new icons to establish its cultural colony in a newly carved West Bengal in the post-partition phase. Chattopadhyay fulfilled the vacuum and became an icon of the community for six decades.

This is a reason, along with Kumar, Chattopadhyay will be eulogised incessantly by the Bhadralok for becoming the character in those visual stories where the community finds itself at the helms of affairs and heaps praise to its achievements, cultures, and way of life, making the aboriginal people pariahs. But this has no significance for millions of toiling poor peasantry, tribal people, Namasudras and Bengali Muslims. They don’t need Chattopadhyay or other Bhadraloks as of now to showcase the milieu in which they live and operate.

Chattopadhyay is neither Apu nor Udayan Pandit, hence he won’t live forever, unlike such a few characters he played. However, mixing up fictitious characters, developed by Bhadralok intellectuals to retain cultural hegemony over the Namasudras and tribal people, with the artists will be a sacrilege of logic. One should refrain from eulogising the man whose political bankruptcy was exposed multiple times. Iconoclasm is essential now to exhibit his political and cultural debauchery so that at least a section of the discombobulated youth can be freed from his cult worship practice.

Unsigned articles of People's Review are fruit of the collective wisdom of their writers and the editors; these articles provide ultimate insight into politics, economy, society and world affairs. The editorial freedom enjoyed by the unsigned articles are unmatchable. For any assistance, send an email to write2us@peoplesreview.in