This year marked the fourth anniversary of the 9th February 2016 Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) ruckus, in which anti-Indian and pro-Pakistan slogans were allegedly raised by the students protesting against the hanging of Mohammad Afzal Guru, the lone convict of the 2001 Parliament attack, who was executed on the same day in 2013. Even after these four years, the echo of the 9th February 2016 JNU row can be felt across the country and instead of dying down, it’s intensifying.

The events of 9th February 2016 JNU row proved to be detrimental for the University and its students. Following the incident, JNU, which previously was considered to be one of the best public-funded universities in the country, was subjected to massive vilification campaigns. JNU not only became the hub of so-called “anti-nationals” but also a den of “free-sex” and drug rackets; a university accused of nurturing “divisive” ideology and an incubation centre for ‘urban Naxals‘. This slanderous campaign against JNU was further extended to question the whole concept of publicly funded education.

Again and again, the rhetoric of taxpayers’ money being used to fund anti-India sentiments was brought up to delegitimise the concept of public funding and easy access to higher education, especially to the marginalised people. The very system of higher education and rationale of research in social sciences and humanities are questioned by the supporters of the ruling party. The ‘age‘ of JNU students has become a butt of a joke!!

Since the 9th February 2016 JNU row, not only the university has been subjected to informal regular vilification campaigns by the ruling party and its blind followers, but it also has been targeted administratively and physically. From arbitrary change in admission policies to bypassing proper rules in recruitment process to banning wall posters — a unique feature of the JNU campus — in the name of public defacement to the latest attempt to hike fees and even a gruesome assault on the students of the campus by feral thugs allegedly associated with the ruling dispensation, JNU has been at the receiving end of a regime which sees any form of criticism and dissent as threatening criminal act.

From what used to be a badge of honour, now JNU has become a badge of shame in popular public perception, thanks to the media trial following the 9th February 2016 JNU row. Today, the students of JNU are seen with suspicion and it has become difficult to wear even the sweatshirts of JNU!! Being a student of JNU, I have faced absurd questions during interviews and social interactions. But apart from having some detrimental consequences for the University and its students, the 9th February 2016 JNU row had other significant impacts on the politics of this nation.

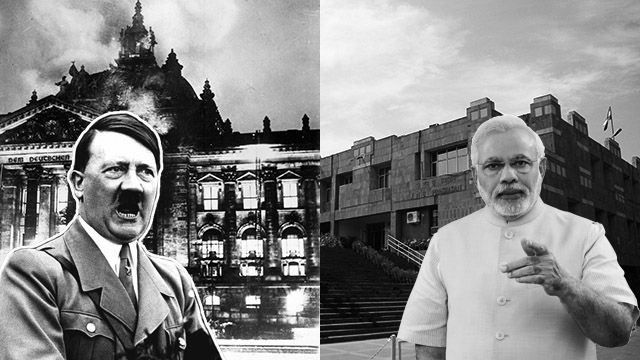

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the 9th February 2016 JNU row proved to be the ‘Reichstag fire’ moment for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Several similarities have been drawn out between the current BJP regime and Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime in Germany. Apart from similarities in ideology and functioning, there is also an interesting similarity between the current BJP regime and the Nazi regime, which can only be called a coincidence.

The ‘Reichstag Fire’, which also happened in the month of February helped Hitler and the Nazi party — from whom the Hindutva fascist movement derived inspiration – to consolidate their power in Germany in 1933. Suspected to be the handiwork of an individual Dutch communist, the Nazi regime used the arsonist attack on the Reichstag building to pass a decree known as Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended most of the civil liberties in Germany and put a curb on Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Press, and Freedom of Assembly, etc, and led to the formal establishment of Nazi dictatorship through the parliamentary path. These basic rights were never again reinstated during the remaining Nazi rule.

February 2016 played a similar role for the BJP. The 9th February 2016 JNU row helped the BJP to consolidate its version of nationalism and strengthen the binary of nationalist–anti-nationalist in Indian politics. Up until 9th February 2016, the term ‘anti-national’ was used loosely and carried little weight; it was used to attack the opposition but the term in itself was devoid of any face and lacked concreteness. The 9th February 2016 JNU row, which was broadcasted live throughout India and the subsequent heated media trials, gave the term ‘anti-national’ a face or many faces, along with ideologies and institutions to identify with.

In the immediate aftermath of the 9th February 2016 JNU rowt, JNU students like Kanhaiya Kumar and Umar Khalid became public enemy number one, the students of JNU became ‘anti-nationals’, JNU as an institution itself became “hub of anti-nationals and enemies of India”. Later, as several political parties, leaders and prominent intellectuals came out in support of JNU students, they too became “anti-nationals” and agents of Pakistan. The 9th February 2016 JNU row helped the BJP to polarise society in its own favour.

From its very beginning, emphasis on the existence of a fifth column which was working tirelessly to undermine the interest of India and to balkanize the nation has been an integral part of the Hindutva theory and movement. The early ideologues of the Hindutva movement, like MS Golwalkar, classified Muslims, Christians, and communists as India’s “internal enemies”. With the kind of alleged slogans which were raised in JNU — a university where student politics was and continues to be dominated by left and progressive ideologies — on 9th February, the theory of the fifth column gained support and found concrete expression and with the help of mainstream and social media, was disseminated across the nation and has been since normalised in the nation’s psyche. This fifth column found its expression with the coining of colloquial terms like “tukde-tukde gang”, “Afzal-premi gang” and later “urban Naxal”. These terms are now part of the political repertoire of the ruling party and their supporters to vilify and delegitimise their opponents.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the 9th February 2016 JNU row also had a significant impact on how dissent was seen in India. Dissent, which is an integral part and life force of any functional democracy, was itself delegitimised and demonised. Every critic of the current government, from leaders of mainstream political parties to individuals, was categorized as anti-national and a member of the “tukde-tukde gang” or was branded as an “urban Naxal”. It also set the grounds for high-decibel media trials in favour of the ruling dispensation with the mainstream press working as propaganda machinery to establish the hegemony of the ruling BJP.

Perhaps, the only difference between the outcome of Reichstag Fire and JNU incident is that while in the case of the former, the incident led to the abrupt introduction of dictatorship, while in the latter case the outcome can be best described as an ongoing process with a high degree of possibility of ending with similar consequences. With ever-increasing interference in autonomous institutions of the state, continuous politicisation of the armed forces, normalisation of hyper-nationalist chest-thumping, continuous attacks on fundamental rights of freedom of expression and speech, and the demonisation of minorities, India is slowly, but steadily, moving towards an authoritarian society. But, on a brighter note, unlike the outcomes of Reichstag Fire which lead to abrupt establishment of a totalitarian regime in Germany, the 9th February 2016 JNU row in the case of India also lead to the development of a new set of vocal political leadership and enriched the vocabulary of protests; it gave voice to the opposition which has to a large extent been banking on anti-incumbency.

Started with Physics and later turned to Comte's Social Physics, Harsh is pursuing a PhD in Sociology from JNU. He is a left student activist and a part-time folklorist.