Although Bengalis commemorate February 21st due to the martyrdom of those who fought in erstwhile East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) for the Bengali language, there is another blood-soaked day for Bengalis in February, which is often ignored. It’s February 18th, the day on which, 40 years ago, the largest and most infamous massacre of Bengalis in post-Partition India took place – the Nellie massacre in Assam.

The massacre took place in 14 villages— Alisingha, Basundhari, Borburi, Borjola, Bugduba Bil, Bugduba Habi, Butuni, Dongabori, Khulapathar, Indurmari, Matiparbat, Matiparbat no 8, Muladhari, Nellie and Silbheta villages — of Nellie under Jaggi Road police station of central Assam’s Nagaon district. Thousands of Bengali-speaking villagers were killed within a few hours on February 18th 1983.

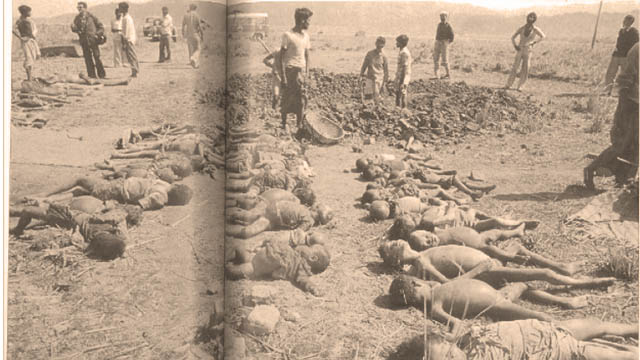

While the official death toll of the Nellie massacre is 2,191, unofficial estimates allege that around 10,000 were killed and thousands were injured, which is much higher than the number of victims of the 1984 Sikh genocide and the 2002 Gujarat anti-Muslim pogrom.

The Nellie massacre was once widely reported in the national and international media. The Indian Express’s Hemendra Narayan and Assam Tribune’s Bedabrata Lahkar wrote extensively on the Nellie massacre. Several documentaries were also made on the subject. However, such extensive coverage failed to fetch justice for the victims of this genocide even after 40 years.

A 1988 report on the Nellie massacre

Journalist Arup Chanda, then an Assam correspondent for Kolkata’s The Statesman newspaper, went to Nellie in February 1988 and spoke to many massacre survivors. His ground report was published in The Saturday Statesman on March 12th, 1988.

The horrific experiences described by the eyewitnesses in that report may sound unprecedented and brutal in India at that time. Still, the optics of the subsequent massacres like the 1984 Sikh Genocide, the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition and subsequent Muslim massacres across the country, the 2002 anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat, the massacre of Christians in Odisha in 2008, the 2013 Muzaffarnagar anti-Muslim pogrom, or the 2020 Delhi anti-Muslim pogrom have turned such bloodbath into mundane affairs in India.

Chanda shared his experiences with the People’s Review in various conversations. He informed about the investigation he conducted on Nellie five years after the incident to showcase how the survivors were faring at that time. This article will try to look back at the massacre based on Chanda’s 1988 report.

Nellie massacre: Causes and the event

Hatred against the Bengalis was instilled in Assam long before independence. Although what’s called Lower Assam was originally carved out of the Sylhet district of united Bengal by the British colonial rulers, who asked Bengali Muslim farmers to cultivate the fertile region and increase the agricultural revenue of the colonial regime, the presence of the Bengali community in Assam has been an eyesore in the eyes of Assamese nationalists. Regardless of their religious identity, Bengalis have been repeatedly subjected to violence and terror in Assam.

The Nellie massacre was a continuation of the “Bangal Khedao” movement in Assam, which began in the 1960s, and the Assam Movement of the 1970s. It was through this genocide that the All Assam Students Union (AASU), the pioneer of the Assam Movement, could sign the Assam Accord with the Union Government in 1985, acting as the representative of the people of Assam.

Soon after returning to power in 1980, the then-prime minister, Indira Gandhi, pitched her Congress (I) party against the Assam Movement. However, her party didn’t achieve significant success at the grassroots level. Rather, the Assam Movement grew ever more violent and powerful.

As this movement intensified polarisation among the people, Ms Gandhi did not take any special steps to suppress it. However, earlier, she had not hesitated to use all her might to suppress the Naxal movement in West Bengal, the anti-Emergency movements between 1975 and 1977, and the Khalistan movement in Punjab.

AASU called for an election boycott during the contentious 1983 Assam Assembly elections. The AASU demanded that the names of alleged “foreigners”, ie, Bengalis who have allegedly migrated from Bangladesh, be removed from the electoral roll. Since almost all Bengalis were “illegal” in the eyes of the AASU, the villagers of Nellie, mostly Bengali Muslims, were also considered enemies. Repeatedly, the leadership of the Assam Movement threatened the people of Nellie to boycott the elections, but the common people defied the diktat.

Late Indrajit Gupta, former Union home minister and Communist Party of India’s member of the Parliament (MP), had alleged that Atal Bihari Vajpayee, leader of the then newly formed Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which now rules both Assam and the Union, visited Assam and allegedly provoked violence against the Bengalis.

Gupta quoted Vajpayee’s 1983 speech during a debate in Parliament in 1996, “Foreigners have come here, and the government does nothing. What if they had come into Punjab instead? People would have chopped them into pieces and thrown them away”. Gupta’s attribution to Vajpayee went uncontested to the Parliament’s lower house Lok Sabha’s records. Such inflammatory speech further heated the tense situation.

Although the villagers of Nellie, like many other places, defied the poll boycott called by the Assam Movement leadership and helped elect Ms Gandhi’s Congress (I) candidate Prasad Doloi, the government wasn’t concerned about the people’s security but only in conducting the election process without any untoward incident.

Assam Assembly elections were held in January and February 1983 in the presence of 400 companies of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and 11 companies of the Indian Army sent by Ms Gandhi’s government.

“This (participating in the elections) infuriated the leaders who threatened a bloodbath after the CRPF jawans, who were posted during the elections, were withdrawn. And they kept their word”, Chanda quoted Alimuddin, whose wife and four-year-old son were killed in the Nellie massacre.

Eyewitnesses told Chanda that the marauders, armed with fire weapons and burning torches, launched a simultaneous attack on 14 villages from the wee hours of February 18th. Other reports claim that most of the attackers were tribals whose ancestors were brought to Assam by the British colonial rulers from Chhota Nagpur.

The mob started firing indiscriminately and set ablaze the thatched huts. Many villagers sleeping in their huts were roasted alive. Those who managed to escape were either shot or hacked. The villagers were stunned by the attack and couldn’t retaliate.

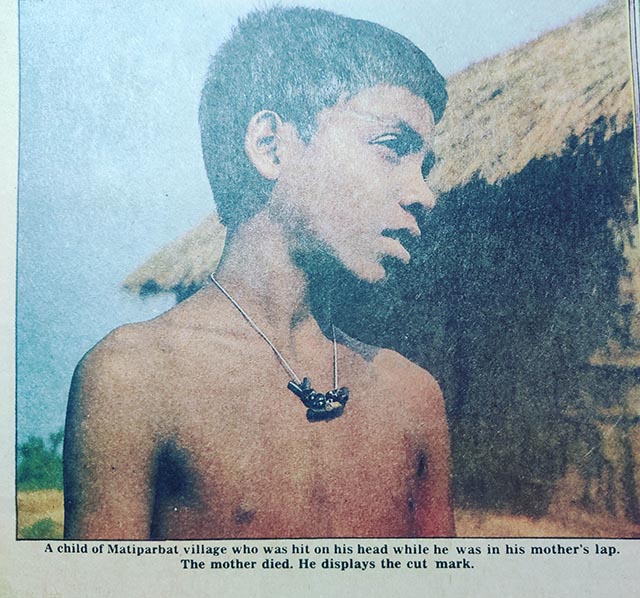

“How could we stop a mob armed with guns? Before we could reach for our sickles and daggers they started shooting us down”, Chanda quoted Mohammad Hazrat Ali, an old man from Matiparbat village.

Some had received prior information about this attack from the local panchayat member Babulal and were prepared beforehand. Many saved their lives by reaching the national highway 11 km away. But the rest were not so lucky. The genocidal forces did not spare the elderly, women, youth, and even young madrasa students.

Chanda’s report states that many villagers, escaping the mayhem, managed to reach Basundhari Bil, the confluence of the Kapili and Kiling rivers. But it didn’t help them. The mob started shooting and killing them from all sides at Basundhari Bil.

Many jumped into the river to save their lives, but when they came out on the other side, they were either speared or hacked to death. Those who somehow managed to escape into the jungle survived for the time being, but many of them died in the jungle from injuries sustained during the violence.

When six truckloads of policemen arrived at Basundhari Bil at noon, the affected villagers gained hope, but that hope was short-lived. Instead of attacking the mob, the police started shooting at the villagers.

Abdul Sattar of Matiparbat told Chanda, “Surprisingly, instead of shooting at the attackers, they fired at us. The policemen, for some unknown reason, kept on firing at us mercilessly”. Sattar also managed to save his family after receiving prior information from Babulal.

The CRPF arrived shortly before sunset. As soon as the CRPF reached the spot, the attackers fled. However, the CRPF fired at the attackers, killing some of them. But by the time the CRPF came and rescued the villagers and took them to the national highway, Nellie had been devastated.

Thousands had been killed; countless families were destroyed forever. But the death march didn’t end there. After February 18th, the victims had to stay in relief camps for several months in miserable conditions. Villagers told Chanda that many children had died of dysentery in those camps.

Nellie massacre: Justice weeps in solitary confinement

The police had filed 688 criminal cases related to the Nellie massacre. Among these, 378 cases were closed due to “lack of evidence”, and chargesheets were filed in 310 cases. However, in the meantime, political developments in India ensured permanent injustice for the Nellie massacre survivors.

In June 1984, Ms Gandhi’s government authorised the Indian Army to launch an operation called “Operation Blue Star” to kill Khalistani militants hiding in the Golden Temple, one of the holiest Sikh shrines in Amritsar. Several Sikh pilgrims were killed in the botched military operation. The bloodbath in the holiest Sikh shrine infuriated the community. In retaliation, Ms Gandhi was shot dead at her residence in October of that year by her Sikh bodyguards. Soon after this incident, the Congress party launched a nationwide Sikh genocide in which thousands were killed.

Ms Gandhi’s son Rajiv Gandhi formed the next Union government following a landslide victory in the general elections. After coming to power, Gandhi signed the Assam Accord with the leadership of the Assam Movement.

As a result of this agreement, on the one hand, the government accepted the demands of the Assam Movement regarding disenfranchising Bengalis, termed as “foreigners”, and on the other hand, the government withdrew all cases related to the Nellie massacre where chargesheets were filed.

Three distinct political streams emerged from the Assam Movement. On the one hand, Prafulla Kumar Mahanta founded the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), which won the elections to form the government in Assam in 1985, while on the other hand, the separatist United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) was formed to continue the violent movement. Also, AASU continued its activities separately from these two organisations.

The survivors of the Nellie massacre compromised with the AGP, as the Congress party couldn’t guarantee them any security, Chanda mentioned in his report. Even though the region’s people voted for AGP’s Moti Das in 1985, the Mahanta-led government withdrew all cases against the perpetrators, using the provisions under the Assam Accord.

While the families of the 2,191 victims of the Nellie massacre were given a compensation of Rs 5,000, the AGP government recognised the attackers killed by the CRPF as “martyrs”, and their families were given a compensation of Rs 35,000.

Nellie massacre and present India

As the Nellie massacre preceded the Sikh massacre of 1984 and the Muslim massacres of 1992 and 2002, the incident served as a precursor to state indifference, strengthening the morale of killers who participated in future massacres.

The Nellie massacre provided a template for all future massacres. It showed that when the perpetrators of mob violence receive political support from significant quarters, they can work with sheer impunity and trample upon all rights guaranteed by the Indian constitution.

Assam’s politics has undergone a sea change since the Nellie massacre. Those who had roots in the Assam Movement and vehemently despised Bengalis and called them “foreigners” have rolled out the red carpet for the ruling BJP. The violence against the Bengalis, irrespective of their religion, continues unabated.

Surprisingly, the self-styled Assamese nationalists have remained tight-lipped regarding the BJP’s communal agenda and its efforts to impose the Hindi language and northern upper-caste Hindu culture on a diverse and culturally rich state like Assam.

Utilising the fissures in the Assamese society, the BJP has used divisive tactics to polarise the society. On the one hand, the government razes houses of the poor Bengalis, unleashes police violence, and stirs communal hatred; on the other hand, using the National Register of Indian Citizens (NRC) provisions in the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003 (CAA 2003), and the Foreigners Tribunals set up as per the Assam Accord, the government continues to disenfranchise Bengalis living in Assam.

In this situation, when the rights of the Bengalis have been undermined, it will be infantile to expect justice for the poor victims of the Nellie massacre organised 40 years ago. The Nellie massacre has set the precedence of providing impunity to the perpetrators of gory atrocities. The impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of the Nellie massacre emboldened all those who took part in future massacres, which shaped India’s politics for over 40 years.

An avid reader and a merciless political analyst. When not writing then either reading something, debating something or sipping espresso with a dash of cream. Street photographer. Tweets as @la_muckraker