Earlier this month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed at an election rally in Jharkhand, that he is poor, owns no property and doesn’t even have a bicycle. But is this true? What does data say?

On Saturday, May 4th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi carried to the podium his characteristic fervour while addressing an election rally in Palamu, Jharkhand. In his signature style, the prime minister proclaimed, with unwavering conviction and without fumbling, that he possesses no assets. Modi asserted that he owns no houses, no cars and not even a humble bicycle. Quite a poor state of affairs for an Indian prime minister! With this, a seasoned orator Modi launched a scathing attack on his political adversaries, the Congress and Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM), alleging that their sole agenda is to amass wealth for their progeny.

Modi stirred this discourse with a passionate defence of the tribal communities who constitute 26.2% of Jharkhand’s population, according to Census 2011. Modi blamed his predecessors for the woes faced by India’s tribals and accused successive Congress governments since the time of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, of ignoring the plight of the tribal people. Modi also projected himself and his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as tireless advocates of the tribal people, claiming they dedicate themselves to serving the interests of the tribal people day and night.

In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, BJP won 12 out of 14 seats in Jharkhand by getting about 56% votes. The opposition JMM-led alliance got only two seats. But even then, the BJP lost the assembly elections in October 2019. JMM came to power. Former chief minister of that government Hemant Soren is in jail today on an alleged money laundering accusation. Soren and his spouse have alleged that Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah have been arrogantly attempting to split his party and topple the government. The JMM also alleged that Soren has been jailed by Modi in a false case of corruption because he is a tribal leader, and the Brahminical character of the BJP infuriates it to see the rise of any tribal leader independent of upper-caste support. But Modi did not say anything about Soren’s allegations of his BJP’s anti-tribal attitude.

Rather, he focused on polarisation.

Using the Islamophobic template that he has been using since his rally in Banswara, Rajasthan, on April 21st, the prime minister stoked the embers of anti-Islamic sentiment in a bid to polarise Jharkhand’s tribal people, who had snubbed the BJP in the state’s assembly elections in 2019.

While marketing his austere lifestyle and alleged allergy to accumulating wealth, Modi used the opportunity to stoke hatred against the state’s minority Muslims, who’ve suffered due to communal violence on several occasions in the past ten years. Modi reiterated his allegation that the Congress will carry out a wealth redistribution programme, through which it would take away the possessions of the tribal people and Dalits and hand them over to the Muslims. He also accused the Congress of plotting to change the Constitution of India to snatch the reservations for the Dalits, tribal people and other backward classes (OBC).

Even though Modi has been indulged in this Islamophobic propaganda for weeks now, acting with sheer impunity, thanks to the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) alleged bias, the claims on his personal wealth in a highly-tensed political battle, fraught with accusations and counter-accusations, embroiled him in a contentious debate.

Is Modi a ‘Fakir’?

Despite claiming that he lives a simple, ascetic lifestyle akin to a ‘Fakir’ (a Sufi monk living on alms), revelations from Modi’s 2023 affidavit paint a contrasting picture. The property declaration filed by Modi on March 31, 2023, says that he has movable assets of Rs 25.8m. Out of which, he has savings of Rs 24.7m in his bank account.

In the affidavit Modi gave while contesting the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, he stated that he had assets worth Rs 25.1m—including Rs 12.7m in bank savings. He then revealed that he also owns a Rs 11m-worth, 3,531 sq ft house in Sector No. 1 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, which he did not inherit but bought after becoming a chief minister in 2002. Although he did not mention this house in the 2023 affidavit.

Amid this display of wealth and makeover of austerity, sobering statistics paint a stark portrait of India’s socio-economic scenario, something Modi denies.

Oxfam’s Inequality Report lays bare the staggering wealth disparity prevailing in Modi’s India, with the top 1% commanding a disproportionate 40% of the nation’s riches, while the bottom 50% fighting over 3% of wealth.

Meanwhile, a 2020 Pew Research study unveils the grim reality of poverty. It shows that in 2020 alone, India’s middle-income group (those earning $10 to $20 per day) contracted by 32m members. At the same time, 75m people were added to the country’s poor (those living on $2 or less a day). It’s alleged that at the same time, the prime minister’s biggest donors’ wealth multiplied faster than ever.

Although many people opposed Modi’s Islamophobic ranting, the Opposition could not attack him for marketing himself as a ‘poor’ man. But if we look at the facts, it will be understood that Modi’s claim is not correct, and he is misleading the poor people of various States, including tribals of Jharkhand, to believe that he’s their representative.

Why Modi isn’t the poor’s representative?

Firstly, as the prime minister, Modi earns close to Rs 1.9m per annum. A skilled worker’s annual wage is Rs 254,580 in New Delhi, the capital city. Most of India’s unorganised sector’s workers don’t even earn that much. Modi earns nearly eight times more than such a worker. Apart from this, he can live a luxurious life at the taxpayer’s expense. The government made a special BMW for his conveyance. The government bought a huge plane for his travel for Rs 80bn. Wearing expensive glasses, pens and clothes has become his trademark.

Secondly, consider the opulence of his political cohorts, the leaders of the BJP, for example.

According to the data of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) and National Election Watch (NEW), 14% of the 225 MPs in the Rajya Sabha or 31 MPs are rupee billionaires. Of these, the highest number of MPs — nine — belong to the BJP. Around 10% of BJP’s total 90 MPs in Rajya Sabha own assets over Rs 1bn. It is followed by five MPs from Andhra’s YSR Congress, four from the National Congress, three from the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (Bharath Rashtra Samiti), two from the Aam Aadmi Party, and two from Bihar’s Rashtriya Janata Dal. The BJP has the highest number of MPs in the Lok Sabha, nine, whose net worth is over Rs 1bn.

Thirdly, what the people of the country remember, even if Modi did not mention it, is that when the electoral bond data was released in March, it was found that the BJP received Rs 55.94bn, which is 46% of the Rs 121.55bn received by all political parties from 2019 to 2024. It means Modi’s BJP is legally the richest political party in India.

Finally, since the formation of Jharkhand in 2000 till 2019, the BJP has been in power in the state for most of the time. In the beginning, Babulal Marandi became the chief minister; later Arjun Munda and Raghubar Das headed the state. Hence, according to Modi’s narrative, Jharkhand had the most tribal-friendly government in the country since its inception. However, the 2011 Socio-Economic Caste Census data shows that 81%, i.e. 1.18m tribal households in the rural areas of Jharkhand, for whom Modi is shedding tears, had a monthly income of less than Rs 5,000. In other words, even after nearly ten years of BJP’s rule, a large section of its tribal masses had to live in abject poverty.

How did Jharkhand fare under the BJP?

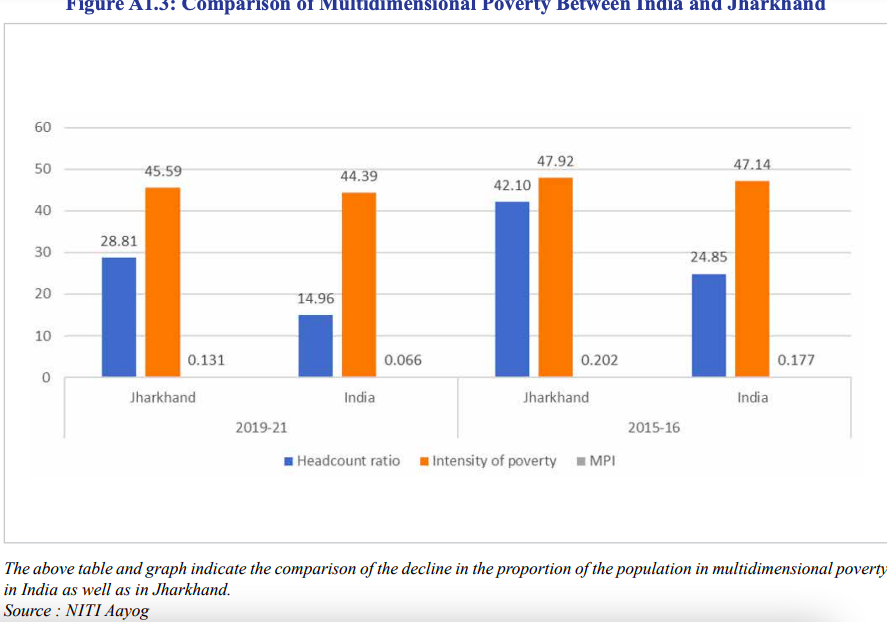

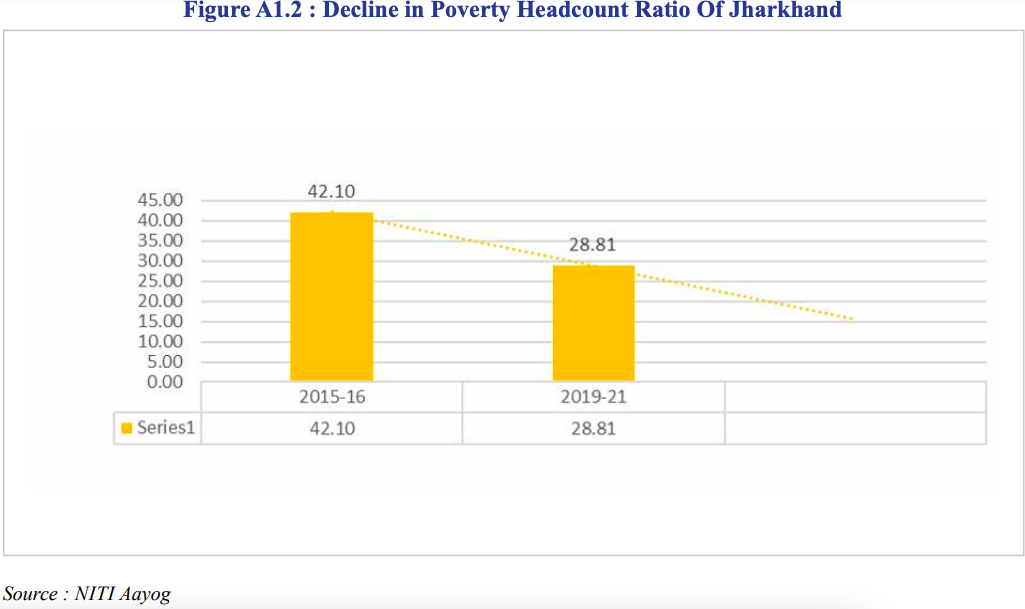

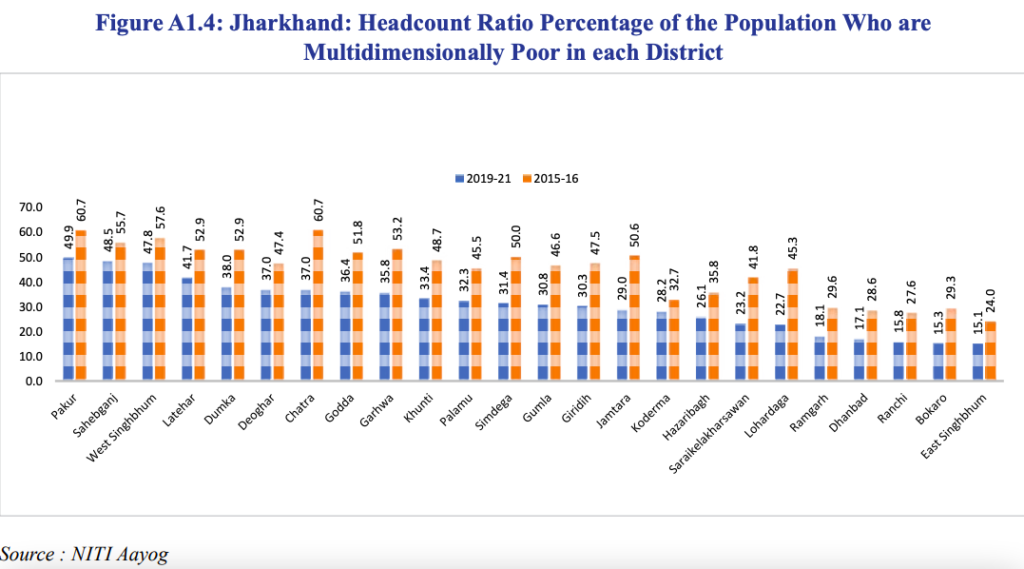

Here is how multi-dimensional poverty fell in the period after 2019 (when the BJP was booted) compared to the previous period, the data from the Niti Aayog shows:

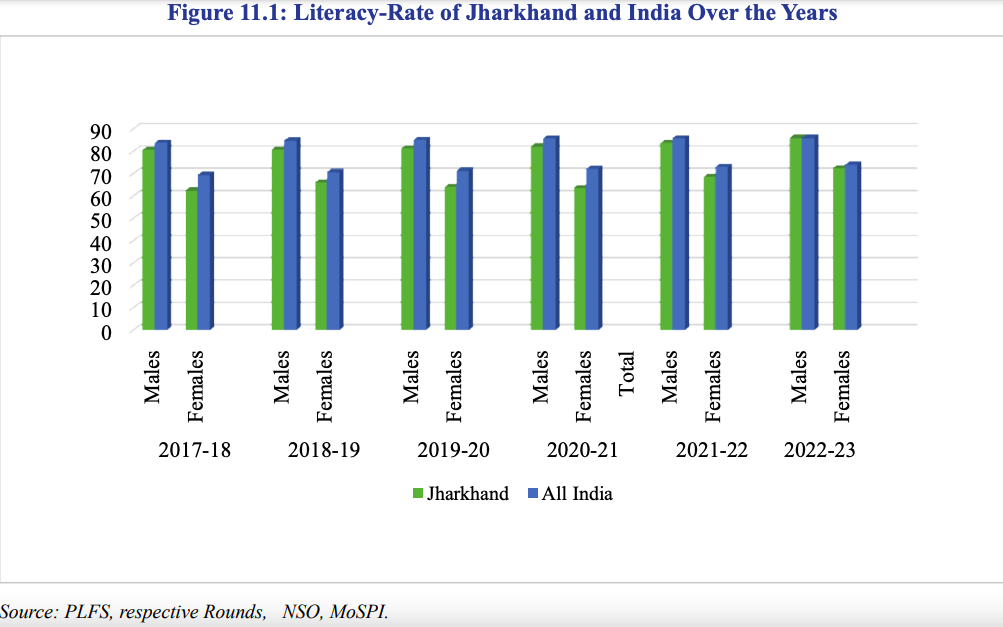

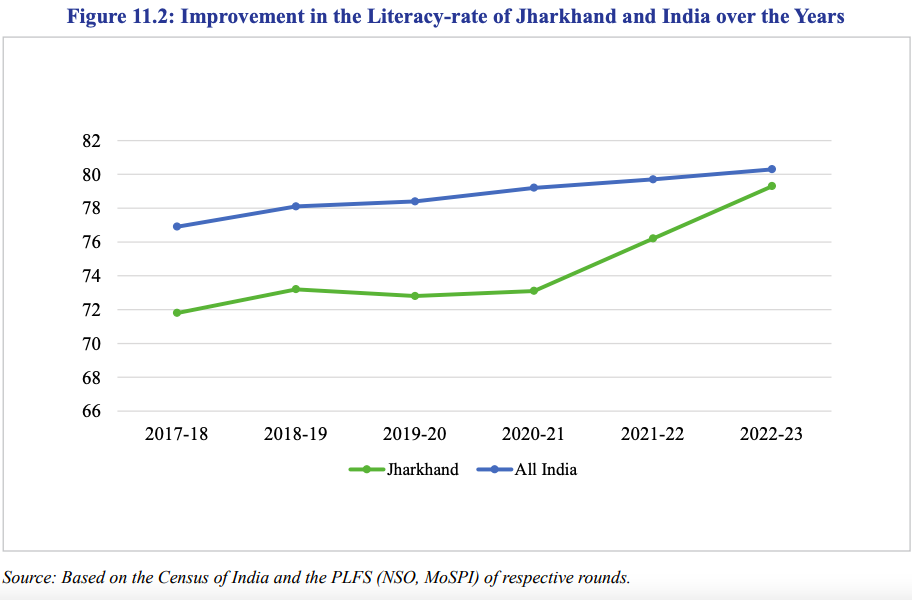

Moreover, one can see how the literacy situation improved, though not drastically, after the BJP was booted out of power in the graph below.

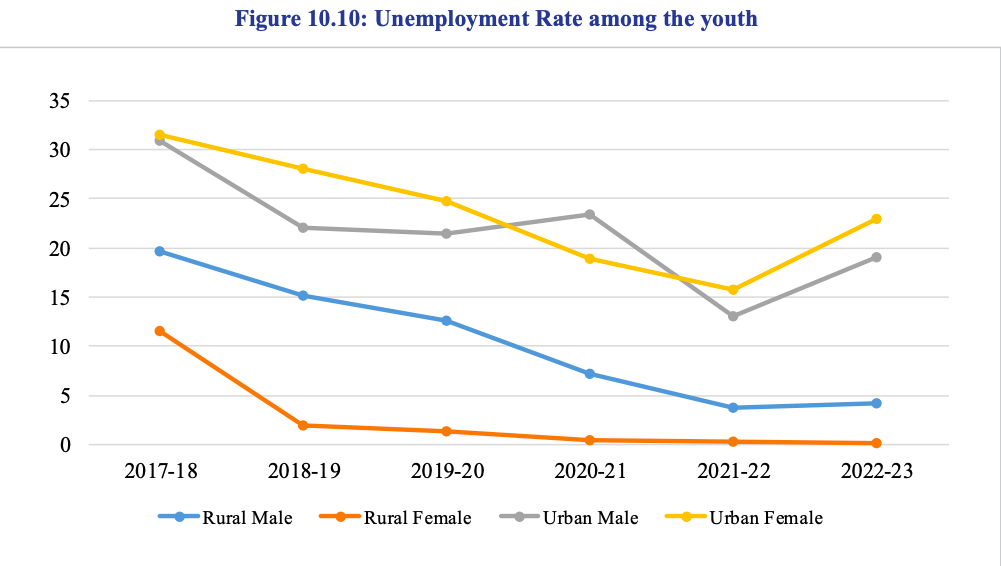

Even the unemployment situation in Jharkhand started improving, although marginally, after the BJP government was ousted in 2019.

As India’s electoral theatre unfolds, the plight of Jharkhand’s tribal communities emerges as a poignant testament to the failure of governance. Despite decades of BJP rule, the socio-economic landscape remains marred by poverty and disenfranchisement. Can Modi escape the blame for it? Mass movements against corporate exploitation, epitomised by the Pathalgadi movement of 2017-18, reflect a simmering discontent among marginalised tribal communities, which acted as a catalyst against the BJP in 2019. And that’s where Modi’s desperation lies, allege his critics.

Denial, unfulfilled promises and the allure of divisive rhetoric

In the face of mounting criticism over its colossal failures, the Modi government’s response has been one of denial and deflection, rather than introspection.

Driven by sheer hubris, it ignores to admit that the economic condition of the poor, especially those belonging to the Dalit, tribal, OBC and minority communities, worsened in the last decade. Promises of development loom like a chimaera, most of the election promises of Modi’s BJP remain unfulfilled, unemployment keeps soaring along with inflation, and education and healthcare have been turned into commodities, yet all these issues are overshadowed by Modi’s communal polarisation drive.

As India stands at a crossroads, the true test of leadership lies not in rhetoric, but in tangible action to uplift the marginalised people, create employment opportunities and foster inclusive growth. But can that be expected in Modi-fied India?

In this tumultuous electoral battle, the people’s verdict remains uncertain. Will they succumb to the allure of divisive rhetoric, or will they demand accountability and progress? Only time will act as the jury and give its verdict, which will have long-term impacts on India’s future.

All data has been sourced from Jharkhand Economic Survey, 2023-24, released by the Ministry of Finance, Government of Jharkhand.

An avid reader and a merciless political analyst. When not writing then either reading something, debating something or sipping espresso with a dash of cream. Street photographer. Tweets as @la_muckraker